Local Government in the U.S.

Local government in the United States occupies a unique and complicated position within the federal system. Unlike national and state government, local government is not recognized and discussed within the U.S. Constitution (Deslatte, 2016). Instead, local government exists as creatures of the state which derive all powers and privileges from their respective state government. This concept, known as Dillon’s Rule, means that in a very real sense, there is no national system of state-local relations, but instead fifty systems of state-local relations (Bowman, 2017). However, it is widely understood that local government is necessary for effective governing and implementation of state and federal policy (Miller & Cox, 2014). Further, state governments generally do not have interest in micro-managing the actions of local government with some going so far as to explicitly empower municipalities of certain sizes automatically through home-rule. To gain a fuller understanding of these institutions as they stand, we must first describe them as they have been.

History of Local Government:

The reform movement of the Progressive Era emerged as a response to the spoils/patronage system of Jacksonian Democracy in which various tools were used to subvert democracy allowing for political machines to effectively pre-determine elections (Martin, 1990). The reform movement resulted in the creation of Public Administration as a profession and field of study. Two municipal forms of government resulted: the commission and council-manager systems, as well as professional organizations such as ICMA. Broader changes were made such as the introduction of a professional federal civil service through the Pendleton Act and abolition of many electoral tools of machine politics such as the long ballot. The most direct way to understand the change in the responsibilities and constraints of local government, is to look at changes in intergovernmental relations between layers of government, also known as Fiscal Federalism.

The Progressive Era was marked by the ratification of the Sixteenth amendment which allowed the federal government to impose a permanent income tax. Even with the income tax, the federal government did not secure a plurality of raised dollars until the mid-1950s (Miller & Cox, 2014). During the early 20th century, municipal government largely funded its own services such as schools, roads and utilities with little input from the state or federal governments (Stephens & Wikstrom, 2006). By the mid-20th century, states began to reform themselves, increasing revenues and revenue sharing, funding of education and institutional reforms; in fact, this is when most of the states adopted their home-rule statutes with Illinois reforming its statute to be particularly powerful. As revenues at the state and federal levels increased and their revenue sharing with local government, so too did the use of conditions on said revenue sharing (Miller & Cox, 2014). During Johnson’s Great Society the federal government sought to utilize shared revenues to enact federal policy on a scale not seen since FDRs New Deal programs. During this time the profession underwent a fundamental shift from Traditional Public Administration to New Public Administration which re-affirmed the social responsibility of government administrators and bureaucrats. During this time, tax revenues at state and federal levels were at an all-time high but through the failures of federal governance and scandals such as Watergate, trust in government would enter a decline it has not begun to recover from in the past half century.

Carter began the agenda of deregulation at the federal level followed by Reagan who greatly expanded deregulation and privatization of government, Californias Proposition 13 severally limited the state’s ability to tax and local governments throughout the U.S. saw their revenue stream greatly constricted by referenda. During this time, tax generating systems quite literally regressed decreasing resources available to those in need while increasing their burden to provide for the meager remains (Stephens & Wikstrom, 2006). This was reflected in the adoption of an overly literal understanding of Wilson’s desire to run government as business (Wilson, 1887) illustrated in the transformation of neighborhood associations from cooperation to corporation via the private homeowner’s association (McCabe, 2011). This transformation in Fiscal Federalism was reflected in the professions’ shift to New Public Management. What followed in the late 20th century and early 21st century was a shift away from vertical intergovernmental relations towards horizontal intergovernmental relations with networked governance coming to the forefront.

Contemporary Local Government:

Local government continues to be a subject of the state, constrained by state constitution, statute, and municipal charter. However, in Illinois, many municipalities enjoy a particularly powerful home-rule statue. Further, due to the shear scale of governmental fragmentation, Illinois local government is spoiled for choice when it comes to intergovernmental cooperation. To understand local fragmentation, we must understand that not all local governments are the same. In Illinois, counties are a general-purpose government and a subdivision of the state that provide basic services to unincorporated areas, maintain property records and other data, county health departments as well as sheriffs’ departments. Municipal governments are general-purpose governments separate from the state that include home-rule and non-home-rule villages and cities as well as townships. Then there is a myriad of special-purpose governments which include special districts (mosquito abatement districts), community colleges and regional governance structures such as the newly established Northern Illinois Transit Authority or Joint Action Authorities. Each of these are public bodies subject to FOIA and OMA with various forms of government and charters/inducing documents. Special-purpose government is the most unique type of local government in terms of form and function as it effectively spans levels of local government from sub-municipal to intercounty and can be designed via special legislation to fulfill any role such as the Central Lake County Joint Action Water Authority.

Municipal governments are formed via charter, prior to the 1870 Illinois State Constitution, the state legislature approved the formation of a new municipal government via special legislation with the current framework for incorporation being introduced in 1872. Since the 1970 Illinois Constitution and establishment of Chapter 65 within the state statutes, the initial form of municipal governments has been largely prescribed with state statute providing for model commission, managerial and strong mayor, aldermanic-city and trustee-village forms of government. Once incorporated, municipalities may alter the exact structure and powers of individual officers as desired via ordinance or referendum. As previously mentioned, the commission and managerial forms of government are resultants of the reform movement.

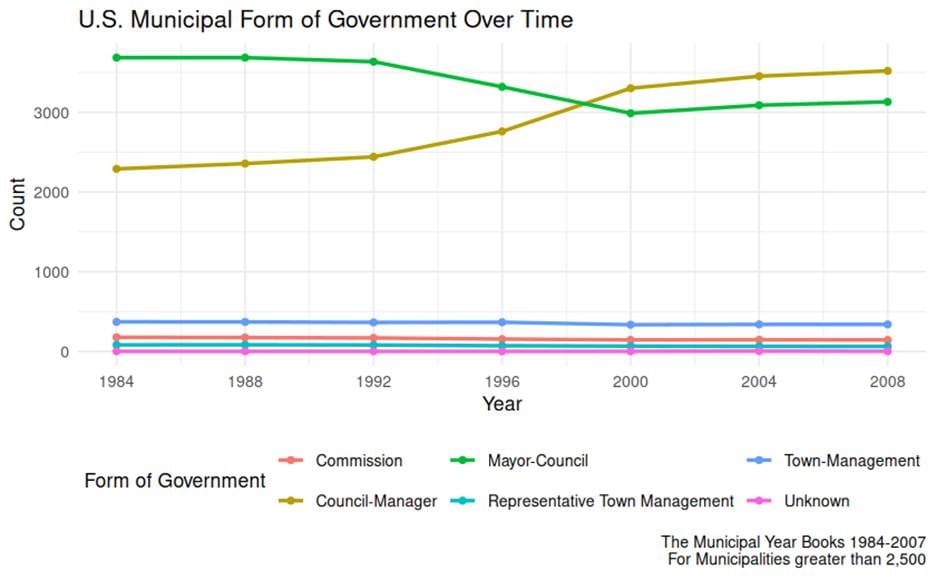

For municipalities with populations greater than 2,500, the Council-Manager form of government has been the most common form of government since at least 2000. Furthermore, many municipalities are opting to retain the council-manager form of government even as they grow into large cities (More than Mayor or Manager, n.d.).

As originally conceived of the Council-Manager system assumes that local government is the resultant of politics and administration and that these processes should be as separated as possible. Descriptive analyses of this form of government in action as well as additional consideration suggests the dichotomy model is too simple to sufficiently describe the world as it is and, if truly implemented, would lead to poor outcomes (Svara, 1985). Instead, these scholars generally observe and argue that while elected and appointed officials should have ultimate decision-making power regarding policy, professional staff nevertheless play a substantial role in agenda setting and issue framing for public issues and in recommending policy solutions.

Local Government in the context of the U.S. federal system is an ever changing and every challenging topic. From subdivision of the state to autonomous private corporations, local governance structures vary wildly in form and function between units and state contexts. While there is no single necessary and sufficient definition of local government, in general we have counties and municipalities which provide services with local special service governments providing public services and goods on a single issue as well as regional special service governments that oftentimes provide a governance structure to enhance and promote collaboration and cooperation. Some local government are deeply reliant upon higher levels of government for funding such as municipalities and counties, with special service governments relying mostly on residents either through ad valorum taxes such as property taxes or pro rata fees such as HOAs. Ultimately however, local government is the closest formal institution which has the power to provide services while being responsive to the mass public and responsibility to provide for the common good.

References:

Bowman, A. (2017). The State-Local Government(s) Conundrum: Power and Design. The Journal of Politics, 79, 000–000. https://doi.org/10.1086/693475

Dahl, R. A. (1956). A Preface to Democratic Theory, Expanded Edition. University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/P/bo4149959.html

Deslatte, A. (2016). Municipal Charters. https://doi.org/10.1081/E-EPAP3-120053329

Feiock, R. C. (2007). Rational Choice and Regional Governance. Journal of Urban Affairs, 29(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00322.x

Gerber, E. R., Henry, A. D., & Lubell, M. (2013). Political Homophily and Collaboration in Regional Planning Networks. American Journal of Political Science, 57(3), 598–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12011

Hefetz, A., Warner, M. E., & Vigoda-Gadot, E. (2012). Privatization and Intermunicipal Contracting: The US Local Government Experience 1992–2007. Environment and Planning C, 30(4), 675–692.

Leland, S., & Thurmaier, K. (2014). Political and Functional Local Government Consolidation: The Challenges for Core Public Administration Values and Regional Reform. The American Review of Public Administration, 44(4_suppl), 29S-46S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074014533003

Martin, D. L. (1990). Running City Hall: Municipal Administration in America. University Alabama Press.

McCabe, B. C. (2011). Homeowners Associations as Private Governments: What We Know, What We Don’t Know, and Why It Matters. Public Administration Review, 71(4), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02382.x

Miller, D., & Cox, R. (2014). Governing the Metropolitan Region: America’s New Frontier: 2014: America’s New Frontier (1st ed.). Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Governing-the-Metropolitan-Region-Americas-New-Frontier-2014-Americas-New-Frontier/Miller-Cox/p/book/9780765639844

More than Mayor or Manager. (n.d.). Retrieved December 9, 2025, from http://press.georgetown.edu/Book/More-than-Mayor-or-Manager

Ostrom, V., Tiebout, C. M., & Warren, R. (1961). The Organization of Government in Metropolitan Areas: A Theoretical Inquiry. American Political Science Review, 55(4), 831–842. https://doi.org/10.2307/1952530

Stephens, G. R., & Wikstrom, N. (2006). American Intergovernmental Relations: A Fragmented Federal Polity. Oxford University Press.

Svara, J. H. (1985). Dichotomy and Duality: Reconceptualizing the Relationship between Policy and Administration in Council-Manager Cities. Public Administration Review, 45(1), 221. https://doi.org/10.2307/3110151

Wilson, W. (1887). The Study of Administration. Political Science Quarterly, 2(2), 197–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/2139277